A cycle in eight parts

The Wheel of Time turns...

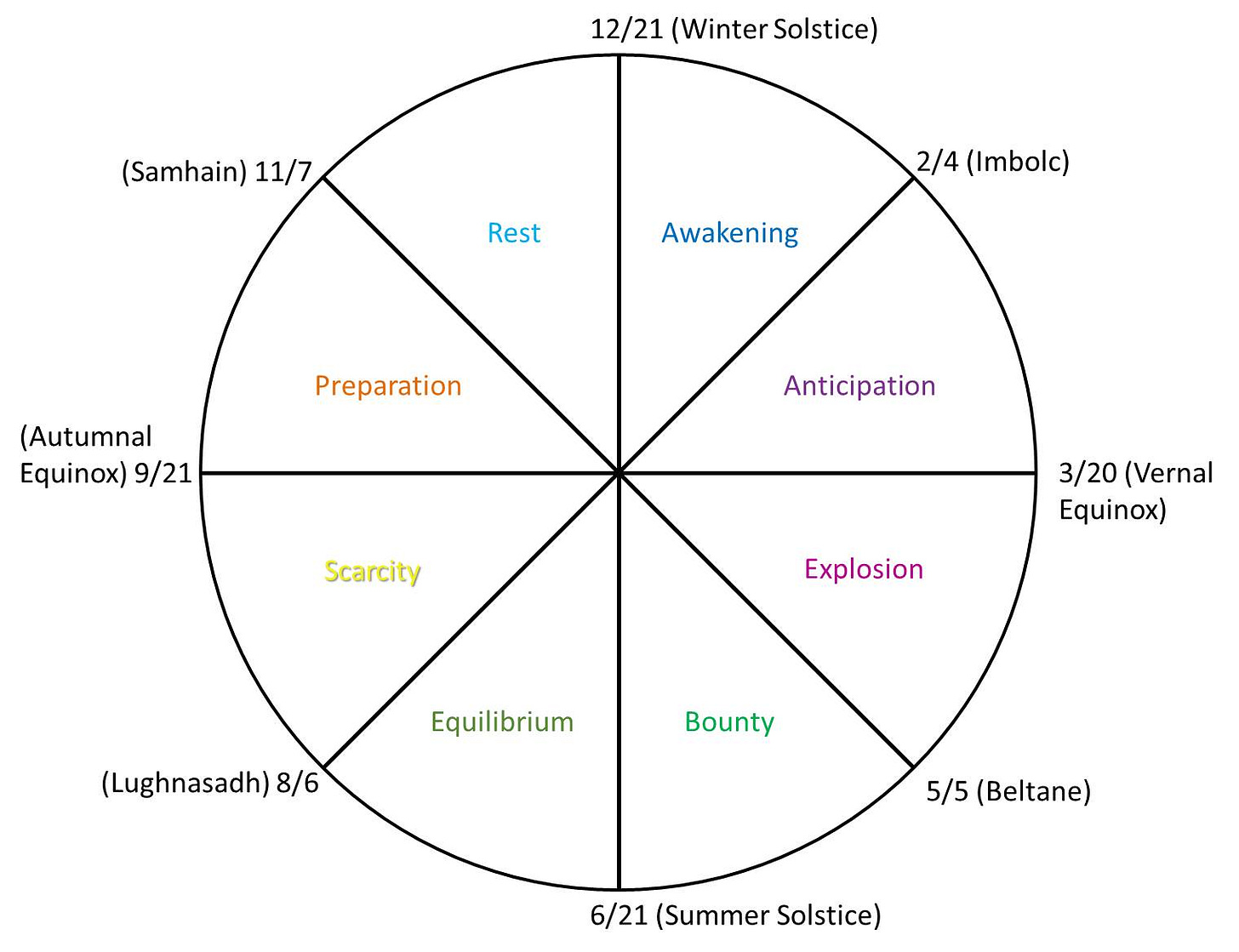

I don’t find the 12-month calendar particularly meaningful. Nothing changes between the last day of one month and the first day of the next, and even the timing of the new year feels a bit arbitrary. To me, the solstices and equinoxes form much more logical divisions: the turning toward light or toward darkness and the midpoints between them. This framework does, however, feel a bit incomplete to me. As I write this, it is still technically summer, and yet it is a very different sort of summer than mid-July or late June.

There comes a time, near the beginning of August, when I realize that the days are getting shorter, that the nights are feeling cooler, that the season of blossoming has transitioned to the season of ripening, that orb spiders are spinning their webs and the evenings keep time to the metronome of crickets. Two Augusts ago, I focused on this turning in my Dendroica writing. This is, in many ways, the beginning of autumn.

There comes another time, usually in the first week of November, when the last fruits have been picked, and the garlic and winter wheat have been planted, and the rains arrive in earnest, and our pantries are full, and we rest by the wood stove and bake pumpkin pies and turn our lives inward, toward reflection and gatherings with friends and family. This is, in many ways, the beginning of winter

There comes a time – one that can be more easily missed – in the beginning of February, when the short days of winter begin to noticeably lengthen, when the weather shifts from all-day rain or fog to showers-and-sun, when crocuses burst into bloom, soon followed by daphnes and daffodils. This is, in many ways, the beginning of spring.

Finally, there comes a time, at the beginning of May, when spring rains taper off, and temperatures soar for the first time, and far-flying birds return from the tropics to nest and fill the mornings with their song, and newly planted seeds burst forth in a riot of growth, and the oak leaves reach full size, and we wish to dance forth in celebration, to frolic around bonfires and sleep under the stars. This is, in many ways, the beginning of summer.

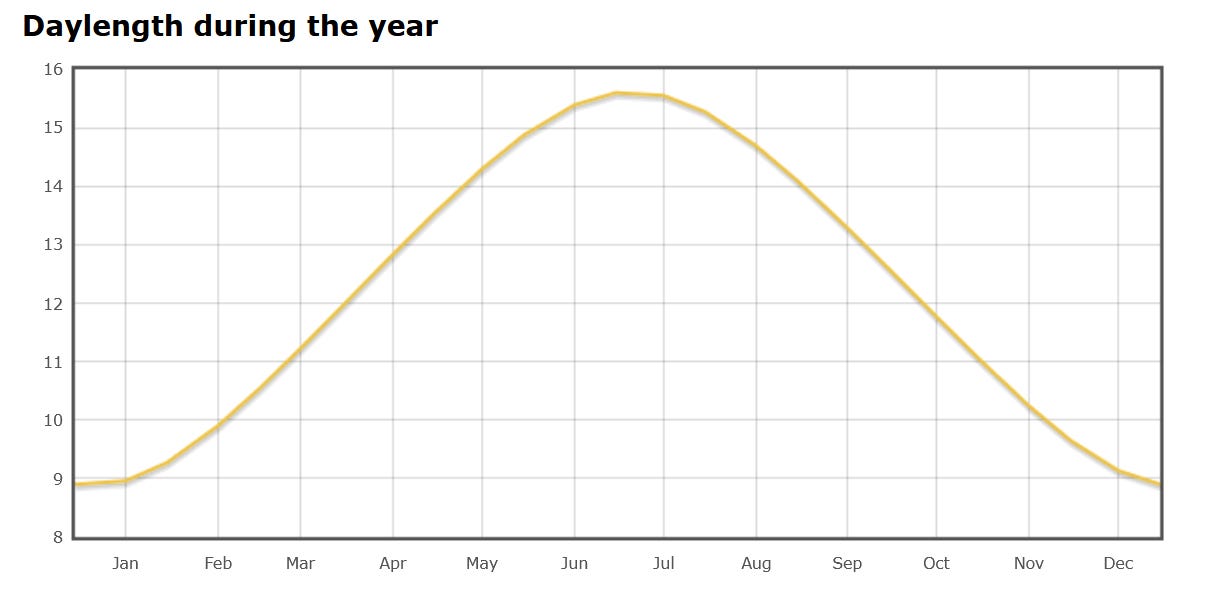

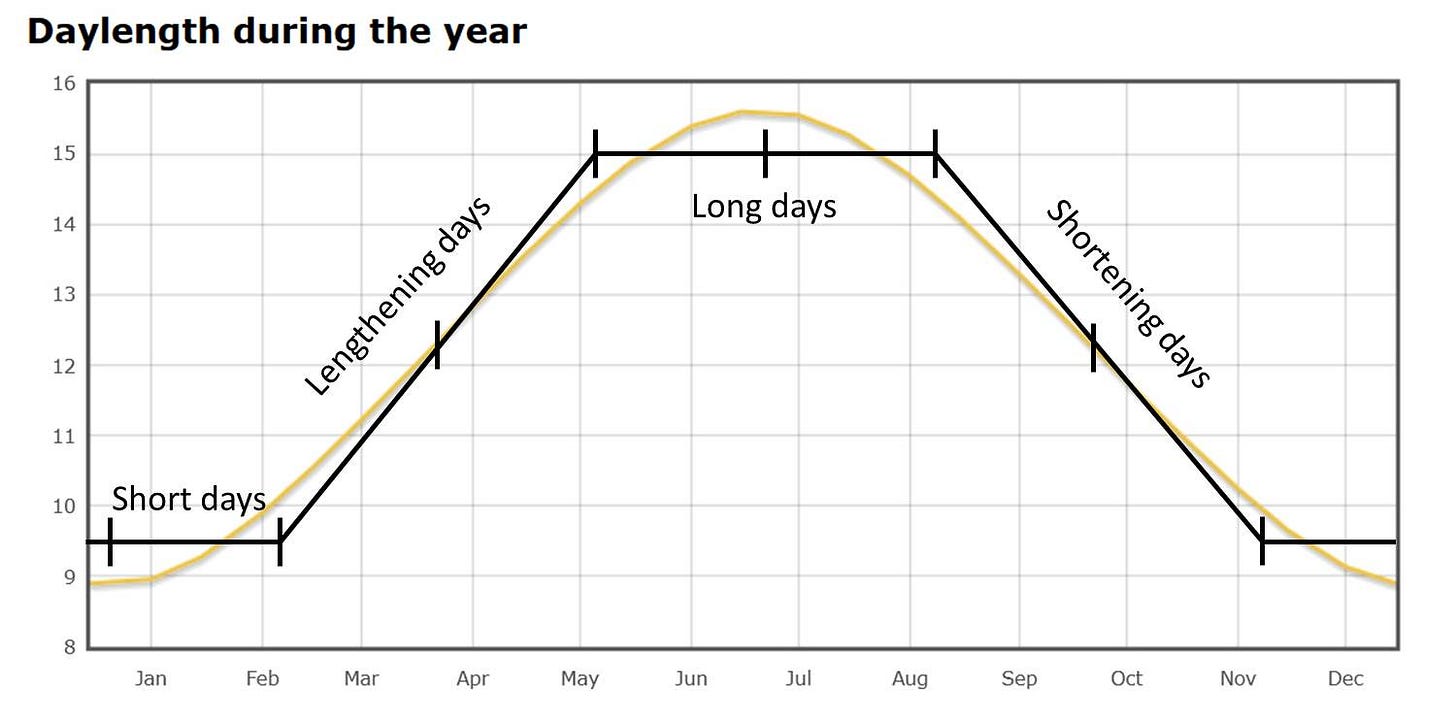

For those of us in the mid-latitudes, if we plot day length or sun angle throughout the year, we see a sine wave. In Oregon, summer days reach about 15 ½ hours from sunrise to sunset, and winter days are a bit under nine hours at their shortest.

If we mark the midpoints between the solstices and equinoxes, we can divide the year into four quadrants: short days, lengthening days, long days, and shortening days. During the three months of short or long days, day length changes by just a little over an hour. During the three months of lengthening or shortening days, day length changes by 2-3 minutes per day and a total of 4 ½ hours.

These midpoints correspond almost exactly with the four shifts that I notice each year in my own experience, and they were celebrated in many cultures and known in Gaelic traditions as Lughnasadh in August, Samhain in November, Imbolc in February, and Beltane in May. These holidays marked the beginnings of their four seasons. In our modern cultures we have preserved Samhain/Halloween/Day of the Dead and – to a lesser extent – Beltane/May Day, but as we have shifted away from connection with the cycles of nature they have lost much of their significance.

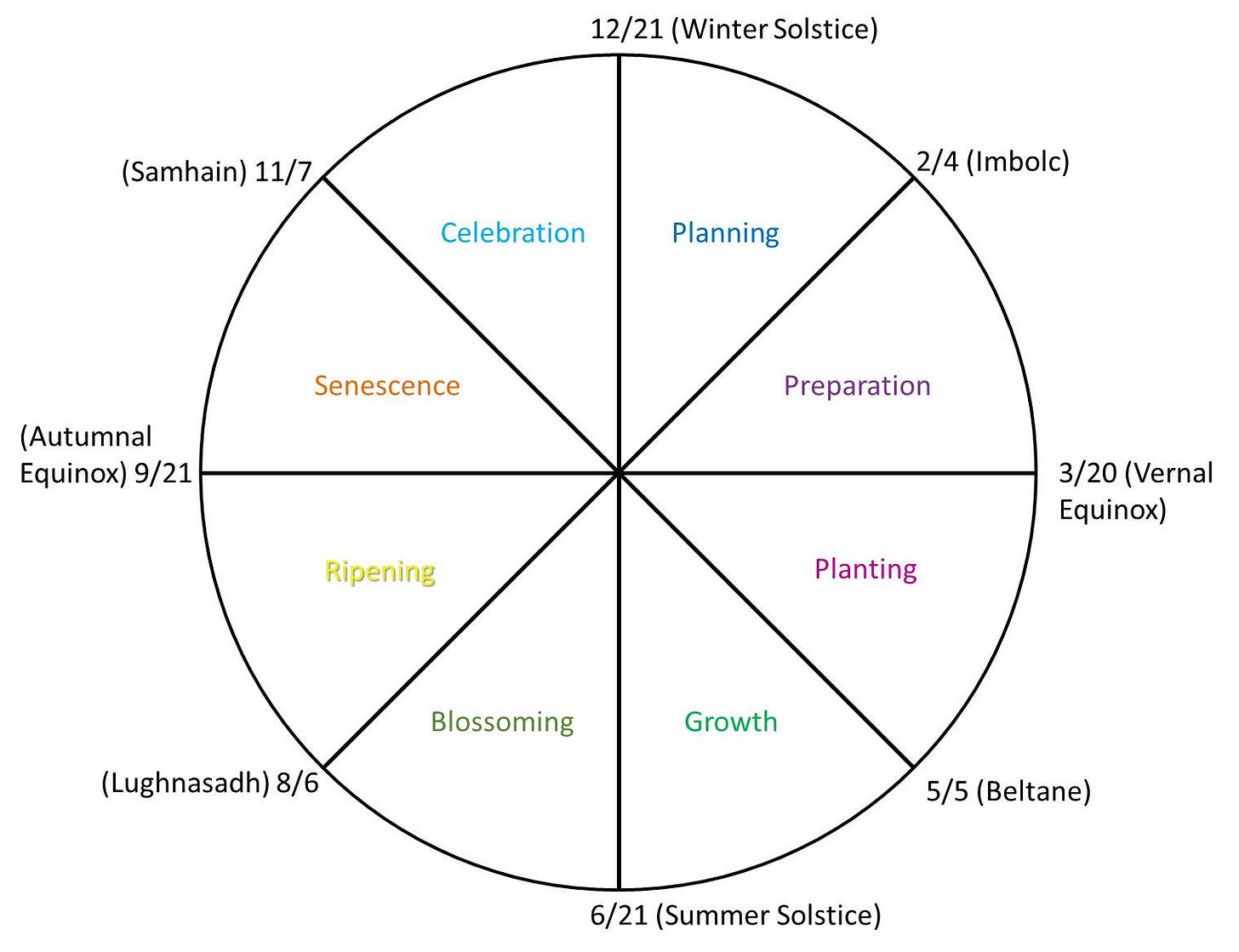

A few years ago I gave a presentation about the annual cycle of beekeeping, and I found it useful to divide the year into eight seasons, using the solstices, equinoxes, and cross-quarter days.

As a gardener and seed grower, the same pattern holds. Imbolc is the time of sowing the first seeds indoors. The spring equinox marks the beginning of planting outside and working in the soil. Most crops are in the ground by Beltane or perhaps a week later, marking the shift from the season of preparation to the season of growth. The summer solstice marks a subtle shift from cultivating and weeding to blossoming and trellising and vegetable harvests. Lughnasadh is perhaps the most significant shift, from growth to ripening, from the time of peak flowers in late July to a rapidly intensifying sequence of harvests: sweet corn, onions, potatoes, quinoa, beans, squash, and all of the spring-planted crops on a seed farm. The autumn equinox marks a subtle shift from a time of ripening to a time of senescence, as fields become brown and bare awaiting winter rains and harvests transition from dry seeds to wet seeds, from vegetables to fruits. Samhain marks a completion, a time when it becomes too wet to work the soil, when all of the summer crops are harvested and all of the winter crops are planted, and we transition to a time of rest and celebration and indoor work. The winter solstice again marks a more subtle shift from a time of seed cleaning and celebration to a time of planning, of deciding what will grow where and ordering the next year’s seeds.

I would love to honor these shifts in a more meaningful way each year, but I don’t feel especially inspired to dance around maypoles or make offerings to old gods. Cultures that honored these cycles created their own traditions, rooted in place and history and mythology. I do not believe we can truly reconnect by simply adopting the old ways, even if those ways were created by our own distant ancestors. I feel we must instead become rooted in place, cultivate immersion and curiosity, and ultimately develop our own traditions that connect to our own rhythms, our own experiences, our own sacred places.

My father excelled at creating traditions. Perhaps, as a former priest and ex-Catholic, he longed for ritual but could no longer find meaning in the traditions of the church. So it was that we came to have solstice bonfires on sub-zero nights, to paint and hide rocks on Easter, to draw numbered stones to choose Christmas gifts, to watch moonrises and measure our moon shadows and celebrate the arrival of the juncos for winter. It was his idea, one summer, to beat a drum gently in time with the crickets as I composed a simple flute melody that we called the “cricket concerto”, to be played at whatever tempo they are singing on a given night.

I have been feeling lately that I need more ritual in my life, both daily and seasonally. So, in the year ahead, I intend to acknowledge these turning points, to experiment with special meals or devotions or gatherings or meditations or pilgrimages that may or may not stick. If it feels rigid or forced or overly think-y, I won’t repeat it. I don’t wish to create a dogma or an obligation, but simply to weave myself more deeply into rootedness, to live more consciously and to remind myself to stay in presence.

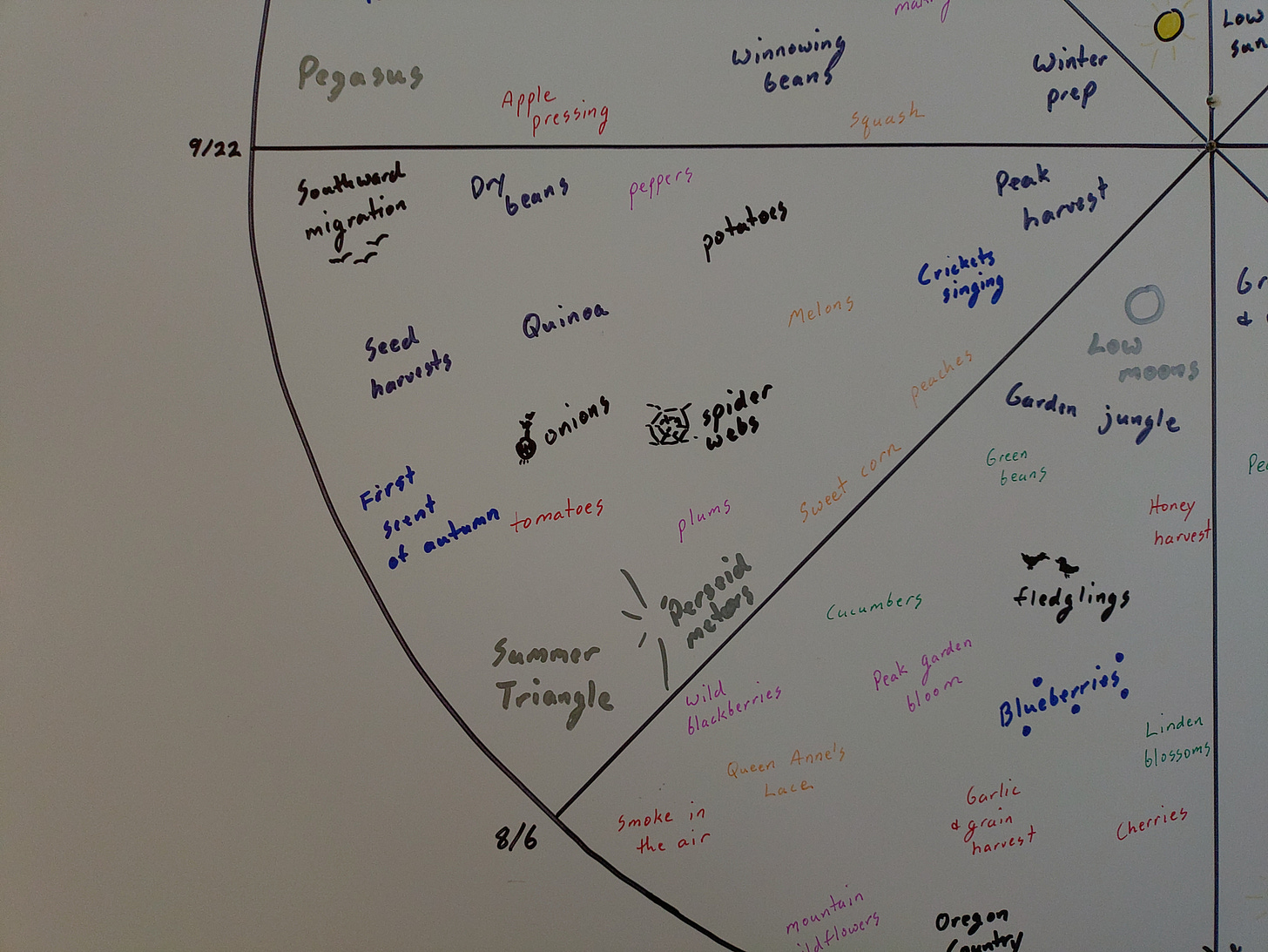

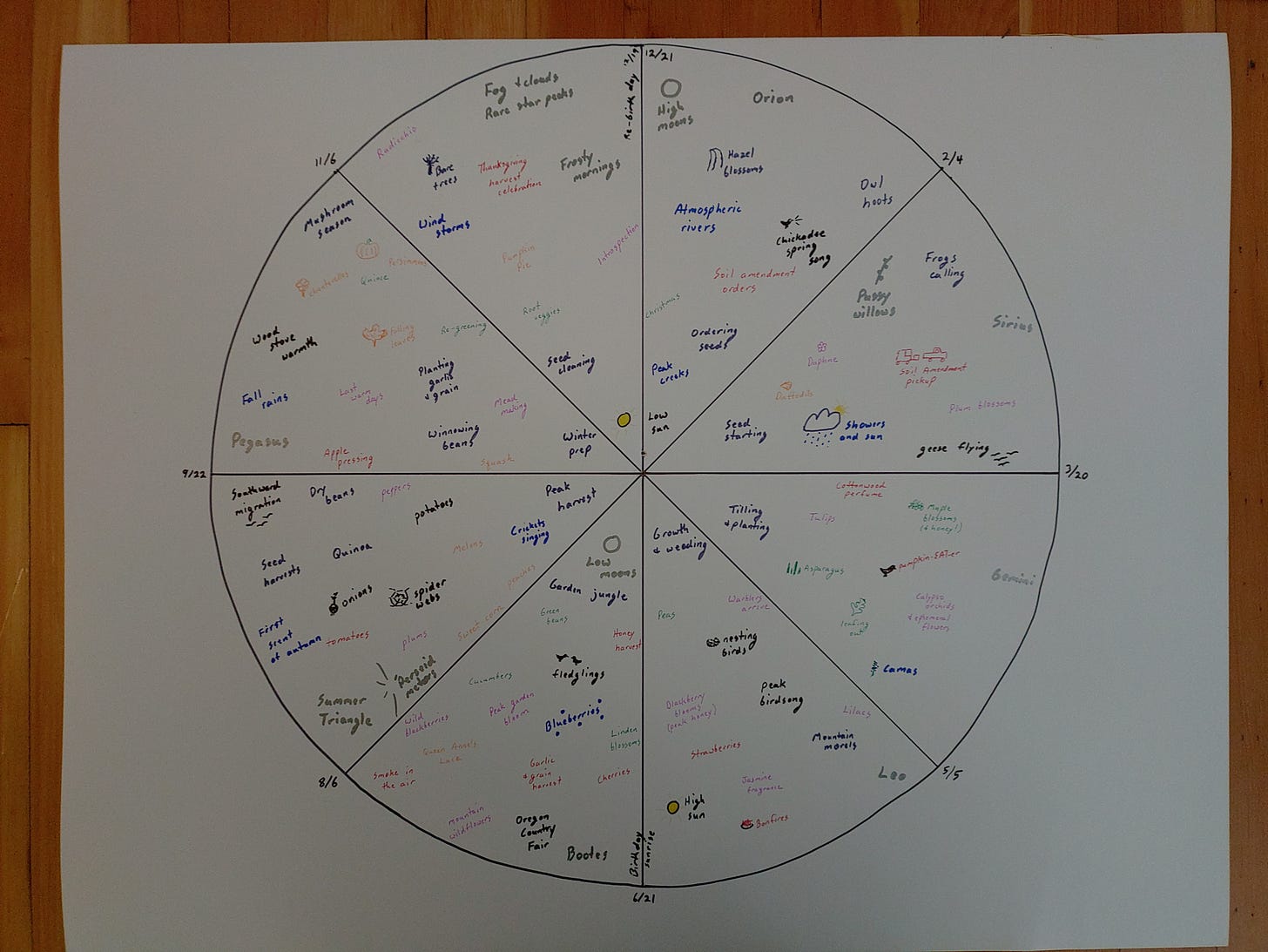

As I was writing this, I felt inspired to create an eight-part wheel of the year for myself, one that I will likely keep adding to until I can’t fit any more. (You can click on the image to expand it.) If this rhythmic framing feels meaningful to you, I encourage you to create your own, to remember and notice the events and turnings that make up your own year, your own Wheel of Time.

Best of luck with your wheel practice — I’m also working on creating more ritual around these occasions this year :)

There is so much I love about this piece Markael. The wheel of the year, with its unique patterns is a devotion for me. I found it interesting to look at the honeybee’s wheel and consider our conversation thread about new year’s and the renewal of cycles.

I resonate with your words here:

“I do not believe we can truly reconnect by simply adopting the old ways, even if those ways were created by our own distant ancestors. I feel we must instead become rooted in place, cultivate immersion and curiosity, and ultimately develop our own traditions that connect to our own rhythms, our own experiences, our own sacred places.”

Yes, I feel this.

I love the idea of creating a personal wheel of the year like you have shown. That seems like such a sweet and meaningful way to bring more attention and awareness to the cycles. Would be a fun activity to do with children.

Lastly, your cricket concerto with your father truly inspires me!