The Earth makes one complete rotation in 23 hours and 56 minutes. Twenty-three hours and fifty-six minutes from now, the stars will be in the exact same locations in the sky as they are at this moment.

We could call this a day. If we did, the constellation Leo would be overhead at - say - 8 pm every evening, but the Sun would rise and set four minutes later each day. Every month, daylight would shift two hours later. Six months from now, the winter Sun would reach its high point at 12 AM, and a year (366 full rotations) from now it would return to the “day shift”, shining high overhead at noon.

If instead we define a day as the time it takes for the Sun to return to the same place in the sky, it grows by four minutes to the familiar 24 hours. The difference arises because as we and our planet travel in a counter-clockwise circle around the sun, while spinning counter-clockwise, we have to spin all the way around and a little bit more to face the sun again. Imagine yourself shuffling from second to third base, facing the pitcher. When you get to third, you’ll have to turn a little bit to the left to keep facing the pitcher. If you keep shuffling around the bases, always facing the pitcher, by the time you get back to second you will have made one complete counterclockwise rotation. This is the same effect.

There are plenty of good reasons to use solar days (24:00) rather than sidereal days (23:56). Our natural cycles of sleep and waking track the Sun, not the stars. However, if we choose solar days, then the stars move daily. Every day, the same star rises four minutes earlier, and so Orion appears in the eastern evening sky in November and moves steadily westward, sinking into sunset twilight in April. With the wider galaxy as our reference frame, the Sun would make a complete eastward circuit of the sky in a year. With our reference frame pointed always Sunward, the stars instead make the same annual circuit, in the opposite direction.

This is probably not a great surprise to anyone, but it is analogous to a similar but lesser-known frame-of-reference timeshift regarding the length of the year.

We are taught that a year is the time it takes Earth to make a complete orbit around the Sun.

This is not actually true.

What we call a year is actually 20 minutes shorter than one complete orbit. What we call a year is the time between two successive summer or winter solstices, fall or spring equinoxes. The reason for this difference is that Earth’s axis is itself rotating, clockwise, very slowly. Picture a spinning top that is leaning a bit and doing slow circles. Earth does this too, but one full rotation, or precession, takes 25,700 years. Each successive summer solstice occurs 20 minutes earlier than a full orbit because Earth’s axis has turned ever-so-slightly to the right, and so we return the point at which that axis tilts toward the Sun a little bit sooner than all the way around. At our orbital speed of 66,600 mph, each successive summer solstice steps backward along our orbit by just under 23,000 miles, or almost three Earth-diameters.

If we chose to define a complete orbit as a year - the sidereal year - then the seasons and solstices would gradually shift, by one day earlier every 70 years. If the winter solstice fell on December 21 in the year zero of our present calendar, it would now land on November 22. In another 11,000 years or so, midwinter would land in June and midsummer would land in December.

As with our choice of solar or sidereal days, it’s fairly easy to understand why we chose the solar year (more commonly called the tropical year) rather than the sidereal year. Our annual cycles of harvests and holidays are more tied to the seasons than to the stars.

Once again, though, if we choose the Sun as our reference, the stars move. In this case, the stars move, ever so slowly, eastward from year to year - one Moon-width every 36 years. Where once the Sun was in the constellation Cancer from mid-June through mid-July, it now transits Gemini during this time. In another 11,000 years or so, the summer solstice Sun will be moving into Sagittarius, and the archer or cosmic teapot that marks the center of our galaxy - now low on the southern summer horizon - will be high overhead in the winter night sky.

Precession presents something of an astrological predicament, because - at least in the most commonly-practiced tropical astrology - the signs are named for the constellations but pinned to the seasons. Aries begins on the spring equinox, always and forever, even though in the time since astrological texts were written about 2,000 years ago, the spring equinox point in the sky has shifted across most of the constellation Pisces and is less than a millennium away from crossing into Aquarius.

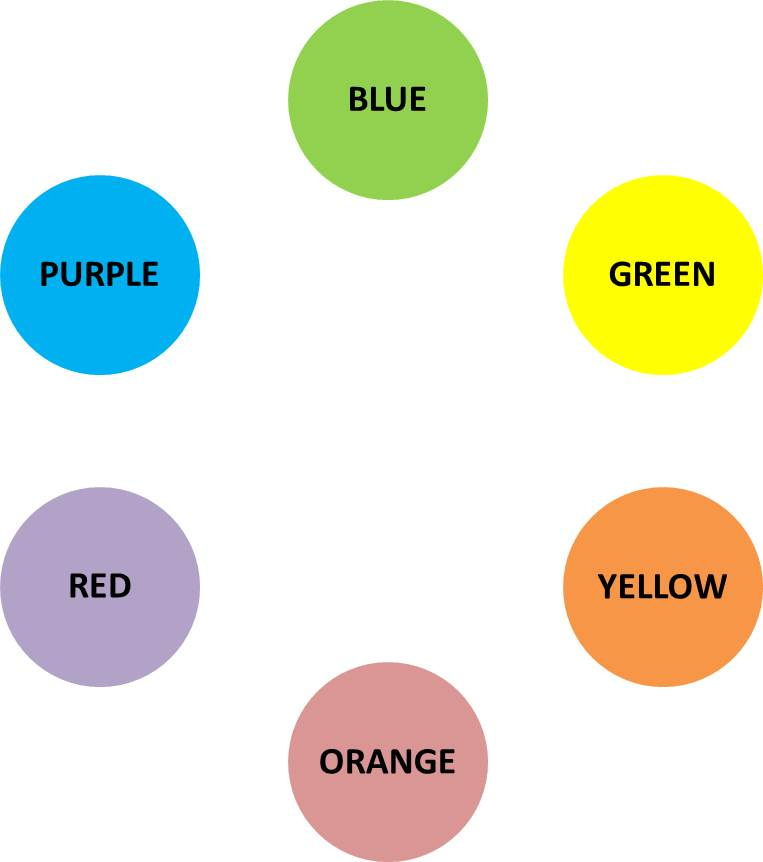

This creates a perceptual/conceptual dissonance, a bit like this:

Today, for instance, astrologers will report that the Moon and Mars are in conjunction in Virgo, but anyone gazing skyward tonight will see them snuggled together up there in the belly of the lion, smack dab in the middle of Leo and not far from Regulus, the star of kings, the lion’s heart.

This mismatch is seldom recognized because - as far as I can tell - most stargazers think astrology is a hokey religion and most astrologers don’t actually look at the sky very often.

Let’s take a step back for a minute.

If all matter is energy, and all energy is consciousness, then we inhabit a living universe. Our planet is, in some ways, like a cell within a galactic body.

If we view things this way, then astronomy is akin to anatomy and physiology. It explores how everything is structured, how it moves on a grand scale. Astrology is akin to endocrinology, functional biology, neuroscience. It explores how the very large affects, informs, coordinates the very small. Astronomy likes to insist that the universe is composed of billions upon billions of billiard balls - from atoms to planets to stars to galaxies - in random and meaningless motion, and astrology has by and large gotten crystallized and codified and divorced from the actual practice of gazing skyward and opening our intuitive senses, allowing in both wonder and wisdom. We have yet another imbalanced polarity, plastered over a reality that feels - to me at least - to be much closer to both-and than to either-or.

And if we return to our mismatch, then we can ask ourselves what means more: the motions of the Moon and planets relative to the rhythm of the seasons or relative to the slow dance of the stars? What means more to a cell in the body: the time in the cycle of sleeping and waking or the position of the whole organism - sitting or walking or swimming or clinging precariously to a cliff? Might this also be a matter of both-and?

There is such a thing as sidereal astrology, that shifts the signs to follow the constellations, but this creates yet another either-or. It is linguistically impossible - or at least exceedingly awkward - to merge the two. Gemini is either a part of the sky overhead at a specific time of year or it is a constellation of stars, but it can’t be both at once, because the two have moved apart and continue to separate in slow but constant motion relative to each other.

So, my humble proposal is that perhaps it is time to rename the signs. They were named for constellations that used to be there but that have since moved along. Since they are pinned to the seasons, it might seem fitting to give them seasonal names, maybe even mythological names. And if the one-twelfth of the sky that begins at the spring equinox point has its own name, then Aries the ram is free to continue his slow eastward walk toward the summer solstice (that he will reach in another 4000 years or so), and when the Moon passes through on each of her orbits we can all look up and agree that the Moon is, in fact, in Aries.

Wow, Markael, just wow. Today is my birthday and this was a stunning read with which to start my next circle around the sun. I'm saving this to read again (and again), and to savor. Your writing is some of my very favorite on Substack, I'm seriously so delighted to have found you. Your perspective is needed, and it is healing. It bends my mind every time!

Loved this so: "If all matter is energy, and all energy is consciousness, then we inhabit a living universe. Our planet is, in some ways, like a cell within a galactic body."